Dyslexia & ADHD: Comorbid and Not a Coincidence

“Dyslexia & ADHD: Comorbid and Not a Coincidence,” by Marie Chesaniuk, Ph.D.

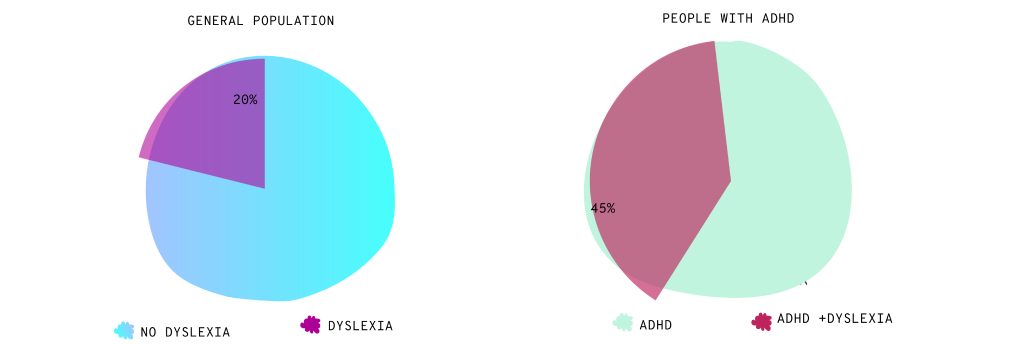

About 10% of school children are estimated to have ADHD (i.e. attention deficit hyperactivity disorder) (CDC, 2023). Separately, it has been estimated that as much as 20% of the general population has dyslexia (also referred to as Specific Learning Disability in Reading; Wagner et al., 2020). However, among people with ADHD, the portion of individuals with both ADHD and dyslexia is estimated to be as high as 45% (Germano, Gagliano, & Curatolo, 2010). Put in visual terms, the pie chart on the left represents the slice of the general population who has dyslexia. The pie chart on the right represents the slice of the ADHD population who has dyslexia. The difference is dramatic and not a coincidence.

How do ADHD & dyslexia relate to one another?

ADHD is characterized by differences in how the brain regulates attention, activity, and impulsive behaviors relative to those without ADHD. Dyslexia is sometimes known as a specific learning disability in reading, though it affects more than just reading. Dyslexia is characterized by differences in the organization of the areas of the brain that process language in spoken, heard, and written forms. In fact, learning disabilities in writing are also more common among people with ADHD (Mayes & Calhoun, 2007). Reading difficulties are more strongly related to the inattentive type versus hyperactive type (Willcutt & Pennington, 2000). Both twin studies and genome-wide linkage analyses of ADHD and dyslexia show some genetic overlap between the two conditions, although the evidence is somewhat mixed. There is no single gene that causes either condition alone or in combination. Children with both conditions may be more likely to struggle with school and develop secondary emotional challenges, like low self-esteem.

While links between ADHD and dyslexia described above explain what arises from co-occurring ADHD and dyslexia, none of these explain what underlies the beyond-chance co-occurrence of ADHD and dyslexia. If the co-occurrence of ADHD and dyslexia is not due to chance, what is bringing these two together?

Brain imaging studies have identified a variation in cerebral lateralization (i.e., where functions are located and how they connect) that impacts language processing across ADHD and dyslexia. In typical brains, certain functions tend to be located near one another and form fast, efficient connections. In both ADHD and dyslexic brains, brain functions, particularly those relevant to reading and language processing, have less specialization to these tasks and often less efficient connections. “Less efficient” means slower processing speed. Processing speed was found to primarily account for the significant correlation (i.e., comorbidity) between the two disorders (Boada, Willcutt, & Pennington, 2012). In ADHD, these differences can be seen in the default mode network’s atypical connectivity. (The default mode network refers to the brain areas responsible for internally focused cognitions, like mind-wandering, introspection, recovering autobiographical memories and assessing others’ perspectives.)

Taking a more scenic route around the brain has pros and cons

Among the cons: it takes longer to get from one area to another, which leads to slower processing speed. Less specialization means that neural pathways stay “scenic” relative to more highly specialized pathways formed in typically organized brains, who dedicate more resources to creating fewer, highly efficient, but conventional, pathways. To put it another way, typical brains form “highways” with only the most necessary off-ramps. They’re smooth, require tons of maintenance and resources to build, but provide the most direct and efficient path to the destination. But what do you see along the way? How easy is it to pave a new path like that if needs change?

Among the pros: the more “scenic” (less specialized) route keeps more possibilities in view. This allows for more creative problem solving and less functional fixedness (White & Shah, 2006; Fugate, Zentall, & Gentry, 2013), sometimes termed lateral thinking or blue sky thinking, which are prized for the generation of original new ideas (Everatt, Steffert, & Smythe, 1999; Tafti, Hameedy, & Baghal, 2009; Gonzalez-Carpio, Serrano, & Nieto, 2017).

These strengths likely reinforce the value of co-occurring ADHD and dyslexia in the world. The next time you’re faced with a dilemma, take the scenic route around your mind and discover what creative ideas you see along the way.

Sources:

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2023). Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD). Retrieved from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/adhd.htm#print on 1/31/2024.

Wagner RK, Zirps FA, Edwards AA, Wood SG, Joyner RE, Becker BJ, Liu G, Beal B. The Prevalence of Dyslexia: A New Approach to Its Estimation. J Learn Disabil. 2020 Sep/Oct;53(5):354-365. doi: 10.1177/0022219420920377.

Germanò, E., Gagliano, A., & Curatolo, P. (2010). Comorbidity of ADHD and dyslexia. Developmental neuropsychology, 35(5), 475-493.

Mayes, S. D., & Calhoun, S. L. (2007). Learning, attention, writing, and processing speed in typical children and children with ADHD, autism, anxiety, depression, and oppositional-defiant disorder. Child Neuropsychology, 13(6), 469-493.

Willcutt, E. G., & Pennington, B. F. (2000). Psychiatric comorbidity in children and adolescents with reading disability. The Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines, 41(8), 1039-1048.

Boada, R., Willcutt, E. G., & Pennington, B. F. (2012). Understanding the comorbidity between dyslexia and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Topics in Language Disorders, 32(3), 264-284.

White, H. A., & Shah, P. (2006). Uninhibited imaginations: creativity in adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Personality and individual differences, 40(6), 1121-1131.

Fugate, C. M., Zentall, S. S., & Gentry, M. (2013). Creativity and working memory in gifted students with and without characteristics of attention deficit hyperactive disorder: Lifting the mask. Gifted Child Quarterly, 57(4), 234-246.

Everatt, J., Steffert, B., & Smythe, I. (1999). An eye for the unusual: Creative thinking in dyslexics. Dyslexia, 5(1), 28-46.

Tafti, M. A., Hameedy, M. A., & Baghal, N. M. (2009). Dyslexia, a deficit or a difference: Comparing the creativity and memory skills of dyslexic and nondyslexic students in Iran. Social Behavior and Personality: an international journal, 37(8), 1009-1016.

Gonzalez-Carpio, Gracia, Juan Pedro Serrano, and Marta Nieto. "Creativity in children with attention déficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)." Psychology 8, no. 03 (2017): 319.

About Us

Learn moreOur Care

Learn moreWhat We Treat

Learn more